salmonkiller

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 28, 2014

- Messages

- 54

- Reaction score

- 0

Takefu Special Steel Co.,Ltd. Interesting read and information.

My personal feeling is that if you want microserrations you can always buy Cutco and let them sharpen them once in a while.

Has anyone actually used/sharpened this knife first hand and can comment on how it feels, performs and why they like of dislike it?Shun is not the only maker to produce dual core construction knives.Does anyone have experience using dual core knives?

Best,

salmonkiller

I think Rick has. The information is higher up this thread. Or maybe the other one

It bugs me that everything they sell tends to be the latest and greatest thing... if everything you sell is the greatest thing ever, then why switch it up constantly... I just tend to look for things a bit more unique.

I wouldn't believe anything Vector Marketing says. Micro serrations are easy just sharpen to a course edge.Seems like it would be a stretch in my mind to compare some college kid pyramid scheme marketing knife in 440A to a coreless damacus steel that has been used by some very reputable knife makers.For some people Cutco products work perfectly fine and the same goes for Shun.Not everyone is a knifenut.That is why I bear the question if anyone has experience with the coreless steel.I am trying to put and hype and marketing aside and asked for an objective opinion about Shuns dual core line.

best,

salmonkiller

At the same time I had read articles saying that antique wootz (the only crucible-grade steel prior to the 1700's) blades were superior to their folded-steel Japanese counterparts. So there is conflicting info here right from the early stages of folded steel in the US. And I'd have to say that the article on wootz has to be less biased as compared to the custom makers hype.

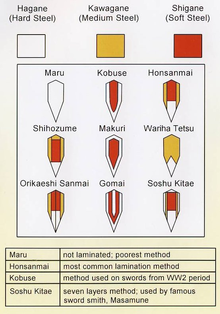

The folded Japanese swords did not necessarily have cladding, though that would have made construction much easier. As I understand the folded billets were constructed so that when the sword blank was pounded out the layers would be .001-2" thick. Making them any thinner would cause carbon migration from the high-carbon layers, any thicker and the sword wouldn't take a good edge. Once the blank is formed there is much metal removal to get it to shape.

You make a good point Tim, given the carbon content of one to the other we are not really comparing apples to apples in terms of what we can possibly be done with modern steels.

Rick

The folded Japanese swords did not necessarily have cladding, though that would have made construction much easier. As I understand the folded billets were constructed so that when the sword blank was pounded out the layers would be .001-2" thick. Making them any thinner would cause carbon migration from the high-carbon layers, any thicker and the sword wouldn't take a good edge. Once the blank is formed there is much metal removal to get it to shape.

They are using this exact same method to make kitchen knives and scissors after the outlaw of samurai class.

The only difference between katana and yanagiba is that in the first case the protein is tougher and not on a cutting board.

The grind is different, a katana's grind is very thick, like an oversized axe so that it won't chip when hacking at bones. Yanagiba lazers thru food but will chip easily due to the thin edge.The only difference between katana and yanagiba is that in the first case the protein is tougher and not on a cutting board.

This is the thing that makes yanagibas bend after being quenched.the curve comes from the quenching

Enter your email address to join: