[Warning that this will probably end up being quite a long post and quite heavy on technical stuff. But I'll try to throw a few pictures in, and it will be fun anyway, because (inspired by

@stringer 's stone above) we're going to have a deep dive into why Washitas look and work the way they do. As ever I'm more than happy to be corrected on any elements of chemistry, geology or anything else, by those that know better. i.e. anyone.]

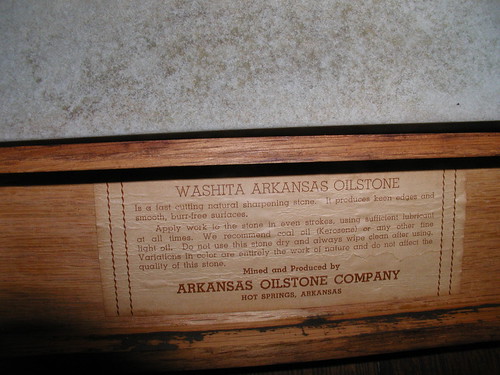

I had a handful of interesting things come up yesterday, here are a couple that might be most relevant to this thread. Found in a fairly amazing old salvage warehouse that I could've spent days in:

View attachment 163308

TBH I might have swerved the broken one, as it's a pretty gnarly break, but your man gave it to me for free when I bought the other and the razor. I'll probably make it into a couple of travel or in-hand stones, as I should get a 4x2 and a 3.5x2 out of it.

I could tell both of them were old Washitas, as there's a fairly distinctive feel and look once you've got your eye in. I can't tell other old dirty stones until I've cleaned them up, but Washitas I usually can.

Here's what they look like after a day or so soaking:

View attachment 163307

Why do they look so different?

I'm glad you asked...

A novaculite is made from tiny bits of silica fused together at a very, very small (micro/crypto crystalline) level. Chemically it's the same thing as a sandstone - both are effectively 100% silica. But a sandstone is large bits of silica (sand), compacted together by lithification, which is what causes the formation of sedimentary rocks. It's quite a strong compaction, but it's nothing like as strong as the more fundamental fusing of much smaller particles, that causes the formation of novaculite.

But novaculite isn't quite just one big bit of silica, because if it was it'd be a quartz crystal. In fact a novaculite is more similar to a piece of flint than it is to a piece of quartz, even though all are effectively 100% silica. Looking at the break in

@captaincaed 's Translucent Arkansas above you can see how it fractures in ‘flinty’ way, and you can you understand why it has been used by people for a long time to make arrowheads &c.

Novaculites are hard, but they're also porous - this quite important in understanding how and why they work as whetstones. These characteristics vary between different types,

and they do not necessarily correlate inversely.

A Translucent Arkansas is both very hard and has quite low porosity. The way that the silica has been fused together is both strong - making it hard, and compact - making it less porous. These are the reasons that a Translucent Ark is slow and fine, and also why it will burnish - because it's non-friable, and why it won't clog - because it has very low porosity. A Soft Arkansas is the other way round, by comaprison it is softer with higher porosity, which makes it coarser and faster, and means it will burnish less quickly because it can shed some particles, though is more likely to clog. The effective 'grit' levels of the two is based far more on the way the structure of the stone is, than on the size of the initial particles, which might be quite similar. It's why people grade Arkansas stones by Specific Gravity, because the porosity and density of the stone has a very large impact on its performance.

A Washita is a bit different because it's both quite hard and quite porous, which allows them to work at a variety of different grit levels. If you work a Washita with pressure you can take advantage of it's porosity and it will work coarsely, but if you use less pressure the fact that it is hard will make it quite fine. The downside here being that Washitas are more susceptible to both clogging and burnishing, it's why dirty old Washitas can feel as smooth as glass. In practice though this may not be so apparent - they're never as hard as hard arks, so if you work them with heavy pressure then new material can be exposed and they won't burnish so quickly.

[The two paragraphs above are, by their nature, generalisations. Any piece of stone is going to be different from any other and all exist on a spectrum. I'm also straying slightly into stuff I don't know about because I've never used a Soft Arkansas, I'm summarizing from what I've read.]

So with the above in mind... why do the two Washitas look so different? Well the blindingly obvious answer, which I realise begs the question*, is because Washitas

do vary quite a lot. The SG of an old Norton Hard Arkansas might be in the range of about 2.60 to 2.65, whereas an old Norton Washita could be anything from 2.0 to 2.5, depending largely on it's porosity. Porosity is what makes Washitas cut fast, examples with very high Specific Gravities will be generally be slower cutting and finer than those with low ones.

Although it seems counterintuitive, in the picture above we might assume that the darker stone with more oil in it is actually

less porous. Here are two other Washitas which I've soaked extensively for many days:

View attachment 163310

One of them is a known and labelled Lily White, but it isn't the one you might expect:

View attachment 163309

This is because they've been soaking in heavy duty degreaser, and oil will come out of a more porous stone more quickly. In the second example the Lily White is one of the highest SG Washitas I have, at 2.45, and the other is the lowest at 2.08. Here's a neat example of a stone that has in areas that are harder and less porous - the dark section in the middle where the oil still is, as well as softer and more porous at the ends:

View attachment 163314

As you might expect the harder sections are also more translucent:

But I've now used both of the initial stones, and they're actually not particularly different. The lighter coloured one is slightly faster and coarser, but they actually both sit around the middle ground for Washitas. So there's something else at play... the age of the stone comes into it too. When I say that Washitas are porous, that's very much a relative thing - they’re not porous in the way a soaking synthetic stone is porous. It still takes many, many years for oil to penetrate down into the stone. If you have a washita with a fresh break or crack in it you'll see the the oil and swarf discolouration only goes a few mms into the stone, the middle is still pure white. I did have a better image of this but I can't find it. Though you can see what I mean here on the chips and breaks:

View attachment 163311

Older stones then will have deeper oil penetration, which will take longer to come out. So of the initial two stones the darker one could be older, or less porous, or both.

And of course there's one last thing that comes into the appearance of Washitas, which can sometimes make them quite difficult to ID even for people who know the stones. You can see it in Stringer's example above, as well as in my 'two-tone' example, and that's the possibility of stones that are heterogenous, or have variability

within the same stone.

This is the basis of the Pike-Norton grading system; Lily White Washitas were not finer or coarser, they were the most homogenous. Look at the old grey-green Pike LW in my pike above and notice how consistent the surface is. Now here's a No.1 Washita, the grade below Lily White, looking kinda speckly:

View attachment 163316

What's interesting here is that these inconsistencies in the stone are not really noticeable initially, when I first degreased that stone it went a very bright, pure white. It is only now after using again with oil that we can see that the stone is not entirely consistent in the way that it absorbs it. Which means that very old stones with lots of oil left in them can appear to be more highly patterned than they would have looked when new. Here's a closeup picture of the darker stone in the initial pictures, after another 12 hours in the degreaser, it's looking, frankly, pretty similar to Stringer's.

View attachment 163324

These aspects of how the composition of old Washitas play into both their usage, and their looks, means that with a bit of experience you can actually ID old Washitas relatively easily, because they're fairly singular stones, even when they look atypical.

---

I hope anyone who's struggled through all of that might have cause to find in useful in the future; when they come across a nice old Washita, can recognise it for what it is, and snag a bargain on one of the best whetstones ever quarried anywhere.

I've moved a few of mine on in the last few months, but I'll leave you with a family pic of all the ones I have atm, which shows a lot of completely white and featureless stones, in all their glorious diversity...

View attachment 163329

---

* I am using this phrase is the original sense - as a type of rhetorical fallacy where the premise of an argument assumes the initial proposition:

Begging the question - Wikipedia . Who knew this was going to be philosophy lesson too eh!