Kippington

A small green parrot

There's a lot of variation in kitchen knives when it comes to distal taper. The topic tends to get glossed over and the details get heaped into one narrow definition, so hopefully this thread will help explain some of the more subtle characteristics of a good taper.

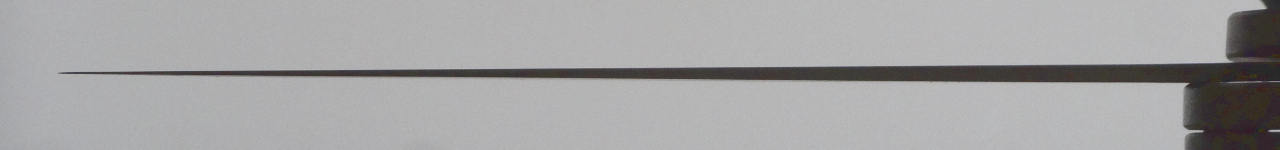

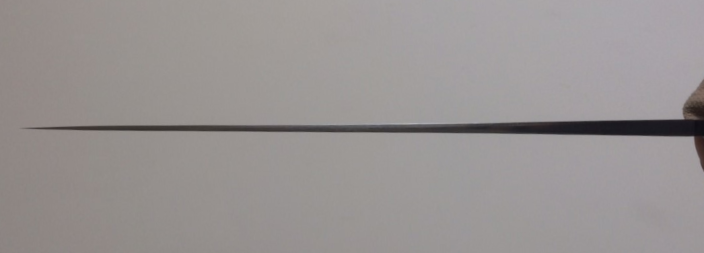

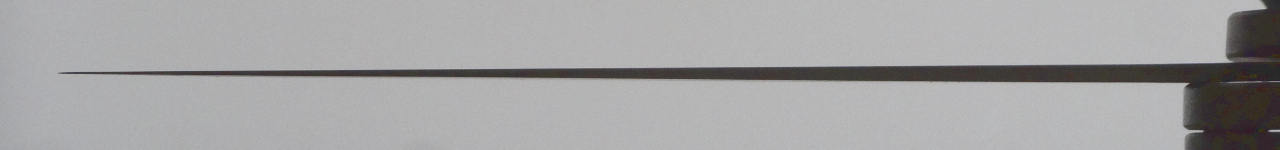

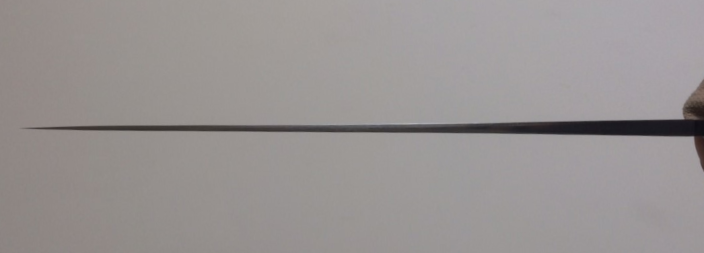

First we should cover what taper looks like from the spine. It can be broken up into three sections - The grip area, the middle of the blade and the tip.

Grip (neck, choil and handle) area

The grip area, or the part of the blade that goes into the handle is the first part we should pay attention to with regards to taper. It's often measured as the spine thickness of the neck, or the thickness of the spine above the heel.

There are three reasons why you would want this to be the thickest part of the blade, the first being comfort. A thicker spine is more comfortable to hold as it allows for more surface area to push down on with your hand. Many cheaper knives (such as Kiwi knives) have extremely thin spines in this area. These make it uncomfortable to push down while cutting through harder foods, as all the force going back up into your hand gets concentrated through a narrow surface.

Similarly, the thickness of the choil down to the cutting edge will influence the comfort of your finger in that area during forward push-cuts. The dreaded Wusthof/Sabatier style full-bolster was designed specifically for this reason, to expand the choil area and increase the thickness where you grip the knife. Other knives will reverse this idea, and have the spine thickness drop dramatically where your finger goes into the choil, while still maintaining a high degree of thickness at the neck.

A full bolster maintaining neck thickness down the choil, plus an example of the reverse

A full bolster maintaining neck thickness down the choil, plus an example of the reverse

Another reason is strength: Many cheaper mass-manufactured knives will have the neck thickness the same as the spine above the heel of the blade. This creates a stress riser at the neck - on thin knives in particular - where the knife is weaker and more flexible at the neck when compared to the stiffer heel and handle on either side of it. Jobs such as crushing garlic with the side of your knife will concentrate forces into the neck, making it more likely to bend in the case of a san-mai/honyaki or crack with a fully hardened blade.

The last reason applies mostly to hidden tang knives with no bolster. A hidden tang can only be is thick as the spine going into the handle, and we want the thickest tang we can possibly get to help increase strength and mitigate any rust that may have been caused by moisture getting into the handle. A thicker neck/spine helps facilitate this improvement, which in turn increases the lifespan of the knife.

Carbon steel knives are more susceptible to rust, but stainless knives are definitely not immune to this phenomenon. A rusty hidden tang, particularly a thin one, is a disaster waiting to happen.

Now it could be argued that some of these points are not part of the distal taper and have more to do with the handle. However, understanding the thickness at this junction helps to explain why distal taper further down the blade is considered to be a positive attribute in kitchen knives.

Now it could be argued that some of these points are not part of the distal taper and have more to do with the handle. However, understanding the thickness at this junction helps to explain why distal taper further down the blade is considered to be a positive attribute in kitchen knives.

Middle area

So taking everything above into consideration, it would seem like we want a super thick spine, right? Well no, obviously a thick a blade will easily get wedged in food during a cut. Naturally we want something thinner in the area where we do the cutting, so we'll need to transition the thick spine of the handle area into a thinner middle section of the blade. There are many ways to do this, it can be done drastically or gradually, and through concave, convex or linear means. We can also use a combination of any of these three methods to create a compound taper.

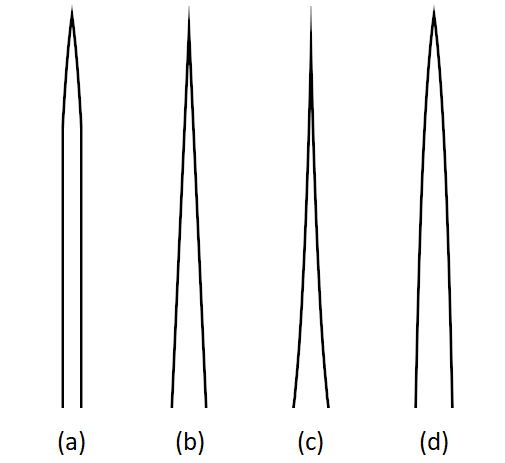

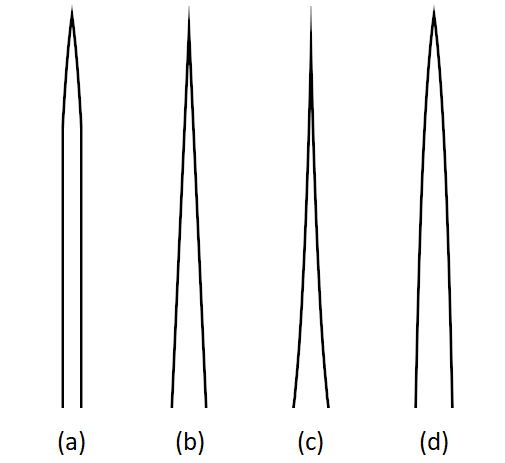

(a) No taper and the thinnest grip area of the four, (b) straight/linear taper, (c) concave taper, (d) convex taper

(a) No taper and the thinnest grip area of the four, (b) straight/linear taper, (c) concave taper, (d) convex taper

As with all things relating to knives, there's a balancing act going on with taper in the middle of the blade. Any positives you might get out of one style will probably increase a negative property, depending on how you look at it. There are four things to take into consideration: Food separation, food release, flexibility and balancing point.

Thinner cross-sections (in conjunction with the grind) can have better food separation and possibly improved food release over a thicker one - more on that below. That said, thinning the cross-section of a knife requires the removal of steel which in turn increases flexibility and removes weight. This can count as a negative thing for some people, as the removal of too much steel can cause a knife to feel whippy and flimsy, as well as sending the centre of balance back towards the handle. Some makers mitigate this by forming a taper at the grip until the blade reaches a certain thickness, then stopping the taper altogether to form an essentially taper-free blade from the middle to the tip. This is an example of one of the many variations of a compound taper, and Kato's style is a good showcase of this.

Tip area

For gyutos, the way a taper ends at the tip is very simple - The thickness of the spine transposes into the grind at the area where they meet. Some people reference sideways slices (e.g. parallel cuts to the board on onions) with the tip of the knife as an indicator for good taper, but really the thinness of the grind is the thing doing the work. You could also use a nakiri to do the same sideways cuts, only the tip of the knife doesn't end at a point. It should be said, having a point can help due to having less surface area in contact with the food, and the lower blade height at the tip means the average thickness of the grind goes down as the spine heads towards the edge, but this doesn't have as much to do with the taper as it does the grind and profile shape.

One important thing to note is that knives with super thin tips will have a lot of flexibility in that area. Some people really dislike any flexibility at all, others don't notice it and might even prefer it for it's related positive attributes (e.g. thinness for sideways cuts).

You can actually test how thin the tip of a knife is by balancing the knife on your finger just behind the centre of mass towards the handle and allowing the tip of the knife to bounce off a hard surface. Thicker tipped knives will clunk but the thinner ones will bounce, giving a surprisingly good indication of how well a knife will perform during the sideways cut.

Taper and balancing point

There are many things that determine the balancing point of a knife, and taper can be one of the more influential factors. If you prefer knives with more forward balance (towards the tip) you'd do well to look for knives with taper that maintains thickness from the neck into the middle of the blade. People that prefer handle-balance should go for extreme taper, and there's obviously an endless amount of possibilities of anything in-between.

Taper and grind/food release

We hear people say that a choil shot can often be an inaccurate representation of the grind of a knife, and the presence of a taper is one of the reasons why.

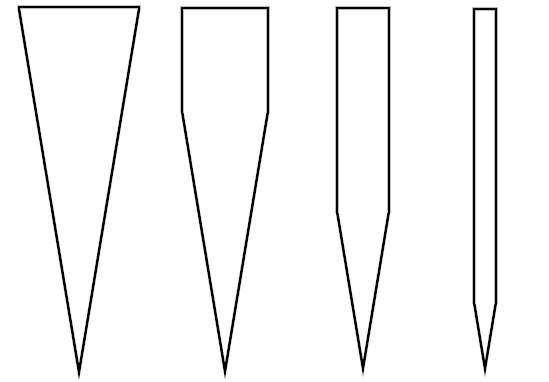

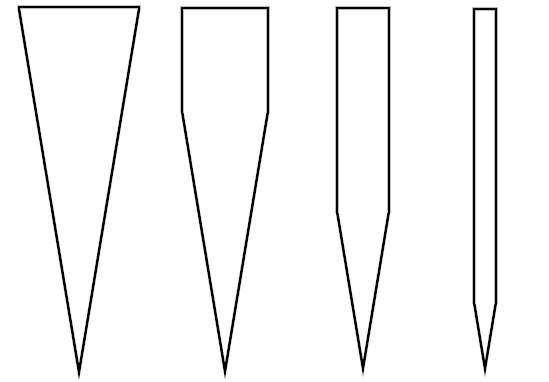

Here is an example of four grinds, each with the same angle at the edge. They may look very different, but it's possible to have all of the four cross-sections occur at different points across the same tapered bar of steel.

The first one on the left is essentially a full-flat grind, known for some of the worst food release possible. As we move right you can see the spine getting thinner, which causes the shinogi line to move down the blade. The example on the far right is where the spine is quite thin and the shinogi has moved down near the bottom of the blade. As you might imagine, the ability for food to stick to the smaller bevel decreases with the shrinking area of contact. This means that the far right example has both better food release and less wedging in food. It's difficult to argue against two advantages like that, so some knife makers create a thick spine in the handle area and drastically shrink it way down as soon as it's out of the grip of your hand. This would be another example of compound taper.

So, that pretty much covers it.

Thanks for reading guys. let me know if you have any questions.

First we should cover what taper looks like from the spine. It can be broken up into three sections - The grip area, the middle of the blade and the tip.

Grip (neck, choil and handle) area

The grip area, or the part of the blade that goes into the handle is the first part we should pay attention to with regards to taper. It's often measured as the spine thickness of the neck, or the thickness of the spine above the heel.

There are three reasons why you would want this to be the thickest part of the blade, the first being comfort. A thicker spine is more comfortable to hold as it allows for more surface area to push down on with your hand. Many cheaper knives (such as Kiwi knives) have extremely thin spines in this area. These make it uncomfortable to push down while cutting through harder foods, as all the force going back up into your hand gets concentrated through a narrow surface.

Similarly, the thickness of the choil down to the cutting edge will influence the comfort of your finger in that area during forward push-cuts. The dreaded Wusthof/Sabatier style full-bolster was designed specifically for this reason, to expand the choil area and increase the thickness where you grip the knife. Other knives will reverse this idea, and have the spine thickness drop dramatically where your finger goes into the choil, while still maintaining a high degree of thickness at the neck.

Another reason is strength: Many cheaper mass-manufactured knives will have the neck thickness the same as the spine above the heel of the blade. This creates a stress riser at the neck - on thin knives in particular - where the knife is weaker and more flexible at the neck when compared to the stiffer heel and handle on either side of it. Jobs such as crushing garlic with the side of your knife will concentrate forces into the neck, making it more likely to bend in the case of a san-mai/honyaki or crack with a fully hardened blade.

The last reason applies mostly to hidden tang knives with no bolster. A hidden tang can only be is thick as the spine going into the handle, and we want the thickest tang we can possibly get to help increase strength and mitigate any rust that may have been caused by moisture getting into the handle. A thicker neck/spine helps facilitate this improvement, which in turn increases the lifespan of the knife.

Carbon steel knives are more susceptible to rust, but stainless knives are definitely not immune to this phenomenon. A rusty hidden tang, particularly a thin one, is a disaster waiting to happen.

Middle area

So taking everything above into consideration, it would seem like we want a super thick spine, right? Well no, obviously a thick a blade will easily get wedged in food during a cut. Naturally we want something thinner in the area where we do the cutting, so we'll need to transition the thick spine of the handle area into a thinner middle section of the blade. There are many ways to do this, it can be done drastically or gradually, and through concave, convex or linear means. We can also use a combination of any of these three methods to create a compound taper.

As with all things relating to knives, there's a balancing act going on with taper in the middle of the blade. Any positives you might get out of one style will probably increase a negative property, depending on how you look at it. There are four things to take into consideration: Food separation, food release, flexibility and balancing point.

Thinner cross-sections (in conjunction with the grind) can have better food separation and possibly improved food release over a thicker one - more on that below. That said, thinning the cross-section of a knife requires the removal of steel which in turn increases flexibility and removes weight. This can count as a negative thing for some people, as the removal of too much steel can cause a knife to feel whippy and flimsy, as well as sending the centre of balance back towards the handle. Some makers mitigate this by forming a taper at the grip until the blade reaches a certain thickness, then stopping the taper altogether to form an essentially taper-free blade from the middle to the tip. This is an example of one of the many variations of a compound taper, and Kato's style is a good showcase of this.

Tip area

For gyutos, the way a taper ends at the tip is very simple - The thickness of the spine transposes into the grind at the area where they meet. Some people reference sideways slices (e.g. parallel cuts to the board on onions) with the tip of the knife as an indicator for good taper, but really the thinness of the grind is the thing doing the work. You could also use a nakiri to do the same sideways cuts, only the tip of the knife doesn't end at a point. It should be said, having a point can help due to having less surface area in contact with the food, and the lower blade height at the tip means the average thickness of the grind goes down as the spine heads towards the edge, but this doesn't have as much to do with the taper as it does the grind and profile shape.

One important thing to note is that knives with super thin tips will have a lot of flexibility in that area. Some people really dislike any flexibility at all, others don't notice it and might even prefer it for it's related positive attributes (e.g. thinness for sideways cuts).

You can actually test how thin the tip of a knife is by balancing the knife on your finger just behind the centre of mass towards the handle and allowing the tip of the knife to bounce off a hard surface. Thicker tipped knives will clunk but the thinner ones will bounce, giving a surprisingly good indication of how well a knife will perform during the sideways cut.

Taper and balancing point

There are many things that determine the balancing point of a knife, and taper can be one of the more influential factors. If you prefer knives with more forward balance (towards the tip) you'd do well to look for knives with taper that maintains thickness from the neck into the middle of the blade. People that prefer handle-balance should go for extreme taper, and there's obviously an endless amount of possibilities of anything in-between.

Taper and grind/food release

We hear people say that a choil shot can often be an inaccurate representation of the grind of a knife, and the presence of a taper is one of the reasons why.

Here is an example of four grinds, each with the same angle at the edge. They may look very different, but it's possible to have all of the four cross-sections occur at different points across the same tapered bar of steel.

The first one on the left is essentially a full-flat grind, known for some of the worst food release possible. As we move right you can see the spine getting thinner, which causes the shinogi line to move down the blade. The example on the far right is where the spine is quite thin and the shinogi has moved down near the bottom of the blade. As you might imagine, the ability for food to stick to the smaller bevel decreases with the shrinking area of contact. This means that the far right example has both better food release and less wedging in food. It's difficult to argue against two advantages like that, so some knife makers create a thick spine in the handle area and drastically shrink it way down as soon as it's out of the grip of your hand. This would be another example of compound taper.

So, that pretty much covers it.

Thanks for reading guys. let me know if you have any questions.

Last edited: